Interview on Native Warriors, Nazi Ideology, and “Butt Stuff” at the Karl-May-Museum

The Karl-May-Museum in Radebeul has been working on new concepts for its presentation of Indigenous North America in recent years, but also on restoring objects and facilities. Some of the objects have been on display almost continuously since the 1930s.

Among them is museum figurine depicting a Comanche warrior, customized for the Karl-May-Museum by Indianthusiast, Nazi party member, and painter of romantic rural Germany, Native American show artists, as well as heroic German soldiers and Nazi storm troopers Emil “Elk” Eber in 1933. When museum staff removed the figurine’s clothing in the presence of some journalists this winter in order to restore the objects and the figurine, they found a swastika painted in red on one buttock, and a Star of David on the other. It is unclear how these symbols got there, and when they were added to the figurine – were they painted on by Elk Eber and/or museum staff during the Nazi era, by museum staff feeling silly at some point during the Communist era (the museum building was refurbished in 1984/85, the figurines could have been worked on during that time, as well)? That issue will remain a mystrery for the time being.

Needless to say, the story of the “swastika on the Indian’s butt” was a field day for tabloid papers and internet news services (nobody was interested why the Star of David was there, too). I was approached for an interview by “t-online.de” a few days later to discuss German Indianthusiasm in the Nazi era and the appropriation of “Indian imagery” for Nazi propaganda.

Our discussion covered a central point that is a major conundrum regarding the Nazis’ racial ideology – why would the most racist of all white racists take a non-white group as role models? We talked about how warrior ideology was useful for Nazis, discussed general notions of anti-Americanism in Germany, but most of all the self-representation of Nazis: They claimed that National Spocialism was the implementation of Social Darwinism, that is, of “natural laws” into political practice and policies. I pointed my interview partner to an article in the Nazi mouthpiece “Völkischer Beobachter” from 1933, titled “Racial Grooming among Indigenous Peoples” (Rassenpflege bei den Naturvölkern). That article talked about infanticide of disabled and malformed children among Native American and Inuit groups, as well as Inuit elders’ suicides during harsh winters, in order to “protect” the group from “unnecessary” or “overbearing” social responsibilities. The article explains the killing of “useless eaters” as a sensible – because supposedly natural – measure of social control and suggests that, while seeming excessively brutal to a “civilized society” such as 1930s Germany, the Natives’ practices were role models because of their intuitive and “natural” efforts to preserve group strength in the Darwinian struggle for survival.

I pointed out that the Nazis, in this argument, sought to prepare the German populace for the euthanasia programs they would put into practice after 1939. In using stories about Indigenous cultural practices as role models, the Nazis conveniently ignored other stories about selfless mutual aid among Native peoples (such as Native leaders surrendering in order to protect their people from further suffering on the run from the U.S. Army), because such stories of submission as the lesser evil would go against Nazi notions of doomsday heroism to the last man and bullet over scorched earth.

The interview was published at t-online on 13 March.

More posts discussing the Karl May museum will follow (hopefully) soon, with reports on conferences about Karl May, as well as current research on Comanche objects in Saxon museums.

Native Americans in World War II – Radio Feature

A little while ago, I was contacted by Markus Harmann, freelance journalist, to discuss Native Americans’ contributions to World War II. Harmann had learned of a West German independent researcher in local history who held a number of war letters from German soldiers during the battle of Huertgen Forest in 1944/45. The letters frequently mention “Indians” among the American soldiers who sneak up to German lines at night to raid German positions and kill unsuspecting soldiers.

This anecdote was a great opportunity to discuss Native contributions to the war, as well as expectations the Native soldiers faced among both Germans and American troops regarding their abilities to fight. Harmann and I looked into what Tom Holm called the “Indian Scout Syndrome” and detail statistics and particular anecdotes. Harmann also interviewed Charles Norman Shay (Penobscot), who participated in the D-Day landing as a medic.

The full-length feature (in German), “Wie American Natives halfen, Hitler zu besiegen“, is broadcast at Westdeutscher Rundfunk (WDR), series “Neugier genügt”, on 6 June, the anniversary of the D-Day landing.

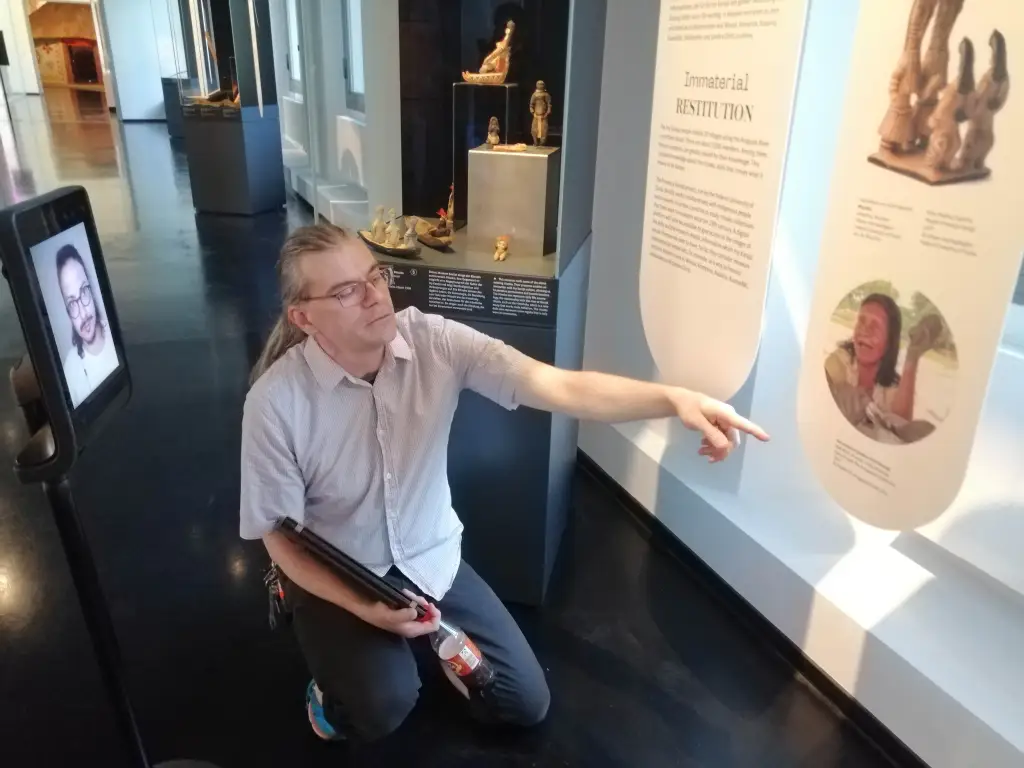

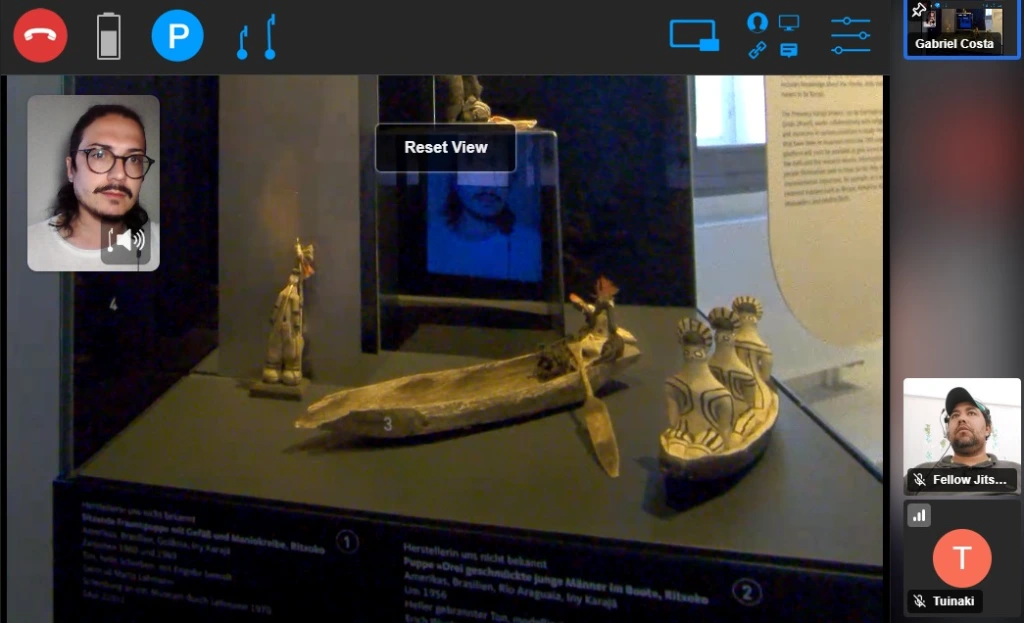

Using Robots for Community Work at the Museum

Research partners from the international project „Presença Karajá“ with partners in Brazil, Belgium, Portugal, and Canada visited our Leipzig exhibition last week using ELIPS (our new fleet of telepresence robots). They took a closer look at the “Room of Remembrance” and at a display of ritxoko dolls from the Iny Karajá in Brazil. Ritxoko are dolls traditionally made of unburnt clay and wax, representing social and gender roles in Iny Karajá communities for children. After World War II, ritxoko were increasingly made of burnt clay, became larger, and are produced also for the tourist market, thus providing a source of income. Their female producers, the ceramistas, are revered in their communities. Ritxoko have recently been listed as part of national cultural heritage in Brazil. The Project Presença Karajá“ seeks to identify ritxoko in museum collections worldwide and to build an online database that is supposed to reconnect Iny Karajá with historical dolls, patterns and production methods, and to serve researchers worldwide.

We have have video conferences with the project group regularly since 2019 in order to study the historic collection of some 80 ritxoko dolls at Leipzig.

During the project meeting in May, a member of the research group remotely steered ELIPS from Canada, while researchers and Karajá representatives in Brazil “moved along”. Our highlight of the tour was when several kids gathered around the laptop of a Karajá representative on the river island Banananal to see a doll which had been collected there in 1908.

It is exactly that kind of interactive exchange that we are looking to enable with ELIPS. Taking it to the test proved how well these telepresence robots serve as tools for collaborating worldwide.

Native Studies in East Germany: After 50+ Years, International Recognition

Part of my research on Native Studies in East Germany concerned the disciplinary history of cultural anthropology at the museums in Saxony (the state-run museums in Leipzig, Dresden, and Herrnhut, and the private Karl-May-Museum in Radebeul), as well as the development of university anthropology in Leipzig after World War II. Because the communist state controlled university enrollment and opened new classes only for as many students as were needed to staff museums and research institutions, there were only a few actors in the field between 1950 and 1990. Historiographical research quickly unveils disciplinary networks among colleagues and former fellow students. Most who studied “Ethnography,” as the discipline was called, at Leipzig or Humboldt University Berlin, later worked together at the museums in Leipzig and Dresden. Unlike developments in “the West,” there was no methodological and theoretical split between museum anthropology and university anthropology in the GDR, so graduates who moved on to different institutions often worked closely together. In addition, the Leipzig museum was a dedicated “research museum”―its research branch was fairly similar to research at the university.

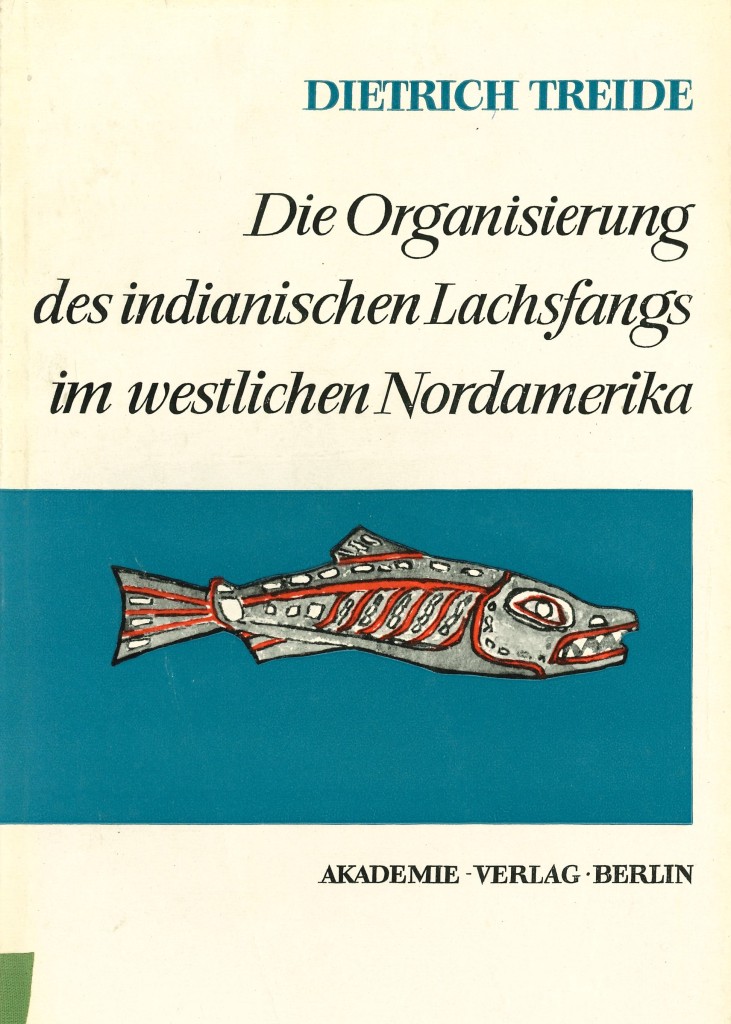

As I dove into the historiography of GDR ethnography, an unexpected opportunity came up early in 2021: Dr. Allan T. Scholz, biologist at Eastern Washington University, approached me about a dissertation defended at Leipzig in 1965. Dietrich Treide’s work “The Organization of Indian Salmon Fishing in Western North America” had been written in German and was reviewed in American Anthropologist in 1966, where the reviewer, Wayne P. Suttles, expressed his regret that the text was only available in German. When Allan Scholz came across this 50-year-old review, he decided to have the German dissertation translated. He approached us at GRASSI Museum für Völkerkunde zu Leipzig about the rights and to obtain some biographical information on Treide.

I’ll document the bio sketch we provided below because it serves to explain the conditions under which a researcher behind the Iron Curtain created a work that, more than 50 years later, is still considered relevant to help build a sustainable fishing industry in the Columbia River basin in collaborative efforts between the US and Canadian governments, as well as the traditional salmon-fishing tribes of the region.

Here is the link to the full translation of the dissertation, with Allan Scholz’s foreword, at EWU’s open access site: https://dc.ewu.edu/scholz/1/

“Notes on the Life of Dietrich Treide (25 March 1933 – 2 November 2008)

Dietrich Treide was a German ethnologist and university professor. He grew up in Leipzig and enrolled in the Cultural Anthropology program at Julius-Lips-Institute for Ethnology at Leipzig University in 1951. The institute had been rebuilt after the war by Julius Lips. His widow Eva Lips took over the chair after Julius’ early death in 1950, one of the first female tenured professors in Germany. The institute was one of two major training centers for cultural anthropology in the German Democratic Republic (GDR, or East Germany). The Lipses had chosen exile from Nazi Germany for political reasons, and spent years in the United States during the war (at Columbia University in New York). They returned to Leipzig in 1947. After her husband’s death in 1950, Eva Lips led the institute into the mid-1960s and shaped the careers of East German ethnographers such as Treide through vivid exchange with researchers from “the West.” She worked to convey a realistic image of North American Indians, and instilled this ethic in Treide.

Unless one’s research focused on communities within the Eastern bloc, GDR ethnographers could rarely hope to receive travel permits for field work abroad, because the Iron Curtain and, after 1961, the Berlin Wall all but sealed off the country from the West. Therefore, a generation of “armchair ethnographers” emerged who were trained to anchor their work around the non-European material culture stored in vast pre-war museum collections (mostly at Leipzig and Dresden) and on diligent ethnohistorical research in the archives. Treide’s dissertation on Indigenous historical fishing economies and social structures along the Columbia River is an exemplary work in this category (1965).

Shaped by the Lipses’ philosophy, Treide’s dissertation shows the influence of American scholars such as Alfred Kroeber, Clark Wissler, and Julian Steward, rather than the ideas of Marxist evolutionary theory prevailing in East German scholarship at the time. However, his work reflects the East German, especially the Leipzig institute’s economic-historical approach to ethnography, and it shows the extensive training in languages and interdisciplinary area studies that became a marker of GDR ethnography. Even while finishing his dissertation, Treide already co-authored a popular survey titled Ethnography for Everybody (Ethnographie für Jedermann) which became a staple on the shelves in East German homes. Such efforts in popularizing academia served to dismantle the notion of scholarship as elitist, and to promote the study of other cultures as a way to diminish xenophobia and racism in post-war East Germany. It also offered a substitute to the wanderlust of East Germans suffering from Cold War travel restrictions.

Taking over the chair of the Leipzig institute in 1968, Treide was often confronted with demands to comply with communist policies on higher education, research, and culture. He was compelled to shift his research focus from “a few irrelevant Indian tribes” to broader – and politically more appealing – observations on the emergence of class and power structures in human history. Throughout his time as chair, he struggled to resist or dampen ideological attempts to steer research and teaching, or to shut down the institute and scatter its extensive historical library holdings. Possibly as a consequence of his inconvenient leadership, he gained tenure only in 1985.

After the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, Treide was elected to lead the reunified German Anthropological Association (1991), a gesture acknowledging his service to the field in East Germany. However, he also felt the shocks and painful changes in East German academia after reunification, which many observers today describe as a “neocolonial takeover” of East German institutes, chairs, and tenured positions by Western scholars and administrators. He lost the chair of the Leipzig institute, and retired in 1996. Together with his wife Barbara, a specialist on Pacific island cultures at the GRASSI Museum at Leipzig, he spent his remaining years on extensive research trips and field studies, and published on cultural identity among communities in the Pacific.

His senior authorship or co-authorship of 54 publications (he was sole author of 34 of them) during his tenure at Leipzig is a lasting testament to his scholarship. His treatise Die Organisierung des indianischen Lachsfangs im westlichen Nordamerika (The organization of Indian salmon fishing in western North America) is a prime example of his scholarship and his portrayal of realistic images of North American Indian cultures.

Frank Usbeck”

Indianthusiasm in East Germany: (Native) American Studies before 1990

In recent years, I have become involved in research on Native American imagery, representation, and Native American studies in the German Democratic Republic (GDR), or communist East Germany. This helped fill a gap in my work, as my dissertation had started out looking into German perspectives on Native people and the emergence of Indianthusiasm in the 19th century, and its eventual implementation during the Nazi era. Later, my research investigated Native images in contemporary nationalist and anti-immigrant discourse in Germany and Europe (see the series of posts around the slogan “Indians Couldn’t Stop Immigration”).

In this new series of posts, I will discuss some work on Native American studies at East German universities and anthropological museums before 1990, and how pop culture shaped interrelations between the communist state, researchers, educators, Indian hobbyists, and the public.

At the GAAS annual meeting in 2021, “Participation in American Culture and Society,” my colleagues Gabriele Pisarz-Ramirez (Leipzig) and Stefanie Schäfer (Vienna) invited me to participate in a round table titled “Im Osten nichts Neues? German American Studies in East and West Germany.” Presentation topics included networks of American Studies behind the Iron Curtain (Charlotte Lerg, Munich), African American studies in the GDR as a perspective on “the other America” (Astrid Haas, Lancashire), the history of the Dresden-based journal Zeitschrift für Anglistik/Amerikanistik (Michael Lörch, Mainz), and the work of the Rockefeller Foundation in early Cold-War West Germany and Eastern Europe (Renata Nowaczewska, Szczecin, Poland). My presentation “Indianthusiasm as International Solidarity” provided a brief historiography of Native Studies in the GDR.

English and American Studies in the GDR were closely tied to teacher training which, in turn, was framed by the strict centralized school curriculum. The bulk of teacher training was taken up by language practice and linguistics. The study of literature, culture, and history of the Anglo-American world, however, only had a peripheral role, and had to fit into the ideological communist framework: US history courses offered brief overviews, mostly skipping the colonial era and early republic, focusing on the Civil War and the US as an emerging global (imperialist) power and, after World War II, as communism’s major adversary in the Cold War. Literature courses covered classic texts and writers (e.g., Twain, Hawthorne, Hemingway), and then drew attention to “progressive” writers, i.e., representatives of the “Old Left,” social criticism, and minority literature, in order to represent the other, “better” America. This focus allowed GDR scholars to carve out a research niche because Western scholarship largely ignored works from within the labor movement, and much of “minority literature” until the late 20th century. Similarly, American-studies topics informed the GDR publishing industry. Apart from new editions and translations of literary classics, left-wing and minority writers were widely translated and published in East Germany.

Native American studies, while a marginal field of scholarly interest, fit into this system and enjoyed a degree of public visibility. Quite a few contemporary Native writers, such as N. Scott Momaday, James Welch, Leslie Marmon Silko, and Louise Erdrich were featured by GDR publishing houses. Silko’s Ceremony was first translated into German by a GDR publisher. Interestingly, quite a few friends of mine who grew up in the West told me that, when they traveled across the Iron Curtain, they usually made a beeline to the next book store because East German publishers were reputed for their high-quality translations.

With just a brief window for my presentation, I could only outline my recent work and hint at fascinating interrelations between university and museum research in Native Studies, ideological directives on how the US and its minority politics were to be presented in museums and classrooms, and how all this tied in with Indianthusiasm. In our lively discussion we found several parallels in the academic treatment and public reception of Native American and African American topics, as both represented the “better America,” and their civil-rights movements were hailed as anti-imperialist currents with which the East German state wanted to identify. These topics also helped students and scholars justify a study interest in the US vis a vis the communist state whose policy-makers perceived any interest in “America” as suspicious.

Regarding Native American studies, I found it fascinating how the historical perspective illuminates current trends in the field – as in other recent discussions, I was asked about Native American reactions to East German Indianthusiasm, and in how far East Germans were aware of cultural appropriation in phenomena such as the many hobbyist clubs or in the DEFA “Indianer” movies. This discussion brought to the fore that cultural appropriation emerged as a concept (and an academic research interest) only in the late 20th century (probably starting with Vine Deloria’s works in the 1970s). Native Studies in East Germany before 1990 were progressive in their “cliche busting” (Glenn Penny) i.e., showing cultural diversity beyond feather-wearing, horse-riding Plains Indians, and highlighting the Red Power movement to show that Native peoples and Indigenous anticolonial/anti-imperialist resistance had by no means disappeared. Cultural appropriation as a concept, however, apparently wasn’t yet on the table, and none of my sources suggest that Native visitors and observers addressed problems we would discuss as cultural appropriation today. It would be interesting to learn, though, how Native visitors to East Germany (there were a few in the 1970s and 1980s, some leading figures of AIM, e.g. Russell Means, and some scholars and political figures, such as Ross Swimmer) reflected on their visits and encounters with communist state representatives, scholars, and hobbyists, once they returned back home.

Announcing Event “Dialogues and Discourses: Talking about Tough Topics in Museums”

The group German and American museum specialists with whom I met for the “Museums 2019” seminar in Washington in November 2019 got together on 21/22 April for a virtual follow-up seminar. We continued our discussions on how museums can reinvent themselves as places for social discourse.

This idea will be further explored in a panel discussion on 17 May, (7 p.m. CET), titled “Dialogues and Discourses: Talking about Tough Topics in Museums“. This event is part of the celebrations of the 75th anniversary of the Fulbright program and was scheduled to prepare the “International Museum Day” (18 May). I will join other panel speakers in a mix of German and US museum specialists, representing four small and large institutions.

The event will be held in cooperation with the Smithsonian Institution and the Leibniz Association.

Please register here by 14 May.

Update, June 2021:

The event on 17 May attracted almost 300 participants. The panel discussion has been recorded and can be viewed here:

Repatriation, Museum Events, and Visitors: Seminar Report, Essay, and Websites

In November 2019, I participated in a four-day seminar titled “Transatlantic Seminar for Museum Curators and Educators: Museums as Spaces for Social Discourse and Learning.” The event was jointly organized by the German-American Fulbright Commission and the Leibniz Association, and hosted at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC.

During the seminar, we touched upon a number of issues relevant for museums today, such as diversity, equity, accessibility, and inclusion (DEAI); visitor and non-visitor (!) studies, outreach and education, as well as repatriation and restitution. The group was very diverse in terms of their museum backgrounds – we had representatives from different museum departments, such as educators, curators, and program managers; and from various types of museums (large and small, private and public, natural history and history, technology, arts, local, and anthropology). As representatives from museums across Germany and the US, we always had the opportunity for transatlantic comparison and contextualization. We learned about other institutions as much as about ourselves in asking: what are the differences and parallels, the opportunities and challenges in museum and cultural politics in the US and Germany, in job descriptions and career development, in the organizational tables of our museums, as well as in our approaches to different topics?

At the end of these wonderfully enlightening and inspiring discussions, we formed groups to develop a number of analyses and best-practice interpretations. The result of this work was now published as a special issue of the Journal of Museum Education (46.1, 2021). I contributed to the group on repatriation.

In our article “Repatriation, Public Programming, and the DEAI Toolkit,” we share case studies in previous repatriations and the corresponding public programs from four museums: the Illinois State Museum in Springfield, the Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Pittsburgh, the German Historical Museum in Berlin, and the State Ethnographic Collections Saxony (Leipzig, Dresden, and Herrnhut) / State Art Collections Dresden. Two major takeouts from our work on the article are:

a) the realization that museums should expand their public programs around repatriation in order to better explain the contexts to local museum communities, as well as to integrate source communities (communities of implication) into the process, and

b) the fact that there is, as of now, little systematic research on public programming around repatriation – we argue that increased efforts and more research on repatriation-related events and education will improve the inclusiveness and accessibility of a museum, and strengthen its networks with both its local communities as well as with the source communities of its collections.

Here are links to various social media posts about the special edition of Journal of Museum Education: https://www.facebook.com/fulbrightgermany/photos/a.2042382882646796/2887745944777148/

While our seminar group worked on the article, my colleagues at the Department of Provenance Research and Restitutions at the GRASSI museum branch of SES further improved our outreach on repatriations and restitution: They opened an exhibition intervention to detail our repatriation efforts and the corresponding projects with source communities. They also launched a website to document these projects and to explain steps and challenges in the restitution process. A number of projects from the Americas, Australia, and the Pacific are already featured here, and more will be added in the future.

The regional broadcasting station MDR interviewed our director, Léontine Meijer-van Mensch, in early March to discuss the new website, as well as previous and ongoing repatriation processes.

Panel Discussion about the Capitol Riots, Cults, and Masquerade

A few days ago, the German-American Institute Saxony (DAIS) held a live-streamed panel discussion on the Capitol riots. Together with moderator Sebastian M. Herrmann (American Studies Leipzig), the panelists, Melissa Gira Grant (The New Republic), Teresa Eder (Wilson Center) and I discussed the inconsistencies and an bizarre manifestations of the event, and contextualized it with the emergence of QAnon and the history of conspiracy theories in general. Considering bizarre costumes and the apparent “happening” character of the event, we asked in how far the protagonists take themselves seriously, and how the costumes play roles in group identity formation, as well as carry political messages. We also put the event in a transatlantic context and compared it with the rise of QAnon in Germany, especially their growing influence in German Covid-protests. In the context of cultural references, I pointed out that Indian imagery has long served to fuel anti-Americanism and xenophobia among the German extreme right and that co-victimization with Native Americans has become a staple feature among right-wing groups across Europe. This reference to “Indians” as the proverbial victims of “illegal immigration” occurs more and more in American anti-immigrant rhetoric as well, notably in the manifesto of the El Paso shooter (2019), and, in more abstract forms, in the bizarre costume of the “Q-Shaman.”

The discussion is available on the DAIS YouTube Channel.

“Posted!”: Panel Discussion on Posters, Cultural Anthropology, and Politics in Indian Country

In late October, 2020 we opened the exhibition “Posted: Reflection of Indigenous North America,” at galerie KUB in Leipzig. Two days later, the Covid fall lockdown struck and all museums in Saxony had to close. The situation will probably not improve before the exhibit ends on 28 February. In order to balance out the canceled opening, guided tours, and lectures, we held an online event on 12 February. The panel discussion was held in German and hosted by DAI Saxony on YouTube. Moderated by SES director Leontine Meijer-van Mensch, Catharina Wallwaey (one of the original Frankfurt student curators of the show), Markus Lindner, (instructor in North American cultural anthropology at Goethe Universität Frankfurt), Robin Leipold (acting director of the Karl May Museum Radebeul), and I worked through questions anchored around the topics of the exhibit.

I was intrigued to learn how the student project evolved, how topics were chosen and background research was conducted, especially since we hope to develop similar student projects in Leipzig. Such a project will have to struggle with cramming all the tasks of research and preparing the logistics of an exhibition into the frame of one or two semesters. Talking about the exhibition also allowed us to present the multimedia guide which SES colleagues developed. Our museum group has been working on a prototype for smart phones and tablets for some time, and the “Posted!” exhibition was the first opportunity for SES to implement this software. We believe it will be a great tool to accompany future exhibitions and projects, either to document the displays, to provide further information, or as a tool for co-curation with students and guest curators.

Commenting on German Indianthusiasm, as well as the challenges of financing and human resources at contemporary museums, we also discussed the role of North American anthropology and transdisciplinary Native American studies in Germany. Our diverse panel (student representative, experts from academia, and curators) offered a great opportunity to iterate concepts for new exhibitions and research projects.

Finally, from among the many topics presented in the poster exhibition, we picked “politics in Indian country” to analyze the implications of the 2020 US-Presidential election for Indigenous communities. We used the great detailed results map recently published by New York Times to show how many Native voters’ tendencies to vote Democrats outlines the borders of reservations on the map. Eventually, we spent some time to speculate what the new Biden administration, especially the nomination of Congresswoman Deb Haaland for the position of Secretary of the Interior, might mean for community interests such as resource development, environmental protection and climate change.

Spoken through the Buffalo (Bull-)Horn: Political Cosplay, Nationalism, and Cultural Appropriation

Our museum joined the discussion around the US presidential election, especially the violence in Washington on 6 January 2021, in a “rapid response” statement. The text was posted on our museum group’s blog. Below is the English translation:

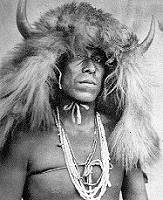

News about the Capitol riots in Washington DC went viral around the globe. Among videos and images of thousands of Trump followers, conspiracy disciples, right-wing militias and Alt-Right activists, large numbers of people in flamboyant costumes dominated the media, most of all Jake Angeli, a.k.a. the “Q-Shaman,” armed with a horned fur headdress, US flag tied to a spear, and large tattoos on his naked torso. The world-wide media response quickly read him as a symbol for the diversity and contradictions among Trump’s followers – for many he represents a hodge-podge of Vanity Fair self-promoter, hypermasculine macho, and a crude motley of cultural and historical references.

Some observers read Angeli’s performance as political cosplay, intended to generate clicks to give the political message more visibility. It is unclear whether Angeli sought to further amplify his message through the metaphor of his bullhorn / megaphone (interestingly, cultural analyses of the role of social media compare blogs to bullhorns*). Other media outlets wondered if the costume was supposed to represent a Viking or an “Indian,” whether the costume elements were ethnohistorically correct, and in how far Angeli committed cultural appropriation in wearing the costume. He himself tends to refer to elements of Native American mythology and cultural practice – to the American bison (who could run you over and trample you to death if you step in its path), and to the coyote, whom Native cultures revere as clever.

In this interpretation, the pick-and-choose of cultural references becomes obvious: Indeed, some Native Plains cultures used bison horns on war bonnets up to the 20th century to acknowledge the deeds and spiritual powers of particularly accomplished warriors. Coyote the trickster plays an important role as a cultural (anti)hero in many tribal creation stories, as well as modern literature, causing mischief and throwing the world out of balance with wanton cunning and laziness.

However, more important than the question of cultural appropriation as such is how these references to Native peoples serve to spread political ideology. White Americans dressed as “Indians” are hardly a new phenomenon in political/cultural history – the colonists who stormed ships and dumped tea into Boston harbor in 1773 to protest British commerce regulations wore “Indian” garb. US cultural memory of the War of Independence fondly recalls that the rebel militias, without a chance against British regulars in pitched battles, learned to use the terrain and to “fight like Indians” in order to defeat the British. Yet, positive references to Native Americans among conservatives and the extreme right-wing are part of a trend that spread from Europe in more recent years.

The reference to Native Americans and illegal immigration is actually a traditional argument among Indigenous and liberal activists in the US to attack xenophobia: “Who is the illegal immigrant here, pilgrim?!” In Europe, especially in Germany, the notion of well-meaning “Indians” overrun by mobs of greedy foreigners has fueled anti-American argumentation since the late 19th century. It climaxed during National Socialism when the Nazis declared that, after the “Indians,” Germans were now the newest victims of American hypocrisy and brutality. Whenever US media protested against the Nazi persecution of Jews, Goebbels’ Propaganda machine retorted with references to “the fate of the Indian.” In 1941, the monthly magazine Koralle exemplified this notion by stating defiantly: “America, Keep Your own House in Order!” During the 19th century, German nationalism had developed a bizarre mélange of ideas about warriorhood and indigeneity that rolled Native Americans, ancient Germanic tribes, and Nordic Vikings into one. Some people claimed Germans and Indians were soulmates, if not blood relatives with a shared primeval proto-Aryan ancestor.

Similar notions and skewed historical comparison abound among the extreme German right today. Massacres against Native villages on the frontier and the near total extinction of the bison are likened to the Allied bombing campaign against German cities during the war. In the last c. 15 years, reference to North American colonial history serves to address a presumed overwhelming of “indigenous” Germans by immigrants (Überfremdung): The slogan “Indians couldn’t stop immigration, and now they live on reservations” appears in right-wing and conservative election campaigns, on Internet memes, bumper stickers, and t-shirts. Like “Indians,” Germans supposedly are on the verge of becoming a minority in their own country. The idea is not restricted to Germany, however – you’ll find the slogan and images in Austria, Switzerland, Italy, Hungary, and in debates on Brexit in the UK.

It seems that the extreme right uses the argument of Indians v. Immigrants strategically. The Norwegian assassin Breivik states in his manifesto (2011) that one cannot drag undecided people off the fence and make them commit to the nationalist cause by idolizing Hitler. Hitler, he says, is ‘burnt’ because his notion of supremacy based on race is no longer acceptable for most people. Instead, nationalists should take on a victim’s perspective and identify with resistance movements of minorities, i.e., they should refer to Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse as role models, rather than Hitler.

In this light, it is not surprising that some US gun-rights activists have begun to portray themselves as victims of oppressive gun legislation and claim that “Indians” lost their fight because they had no guns. The El Paso shooter commented in his manifesto (2019) that “Indians” couldn’t stop immigration and, therefore, Americans today had to learn from their plight and use violence against immigrants and refugees on the Mexican border (apparently, he wasn’t aware of the historical irony). So, Angeli’s bizarre attire continues a trend that has a longer tradition among nationalist groups but has taken hold in the US only recently. Despite all the ludicrous elements in his and others’ performances, then, this development is a sign of the increasing internationalization of right-wing extremism. It is a practice with a long history in Germany. The images of the storm on the Capitol are unsettling not least because the violence depicted there is also part of everyday life in contemporary Germany.

*J. W. Rettberg, Blogging, 2008. 64-66: F. Usbeck, Ceremonial Storytelling, 2019, 154-56)